Day of the creole song: Get to know the Old Guard of Peruvian criollismo

Síguenos en:Google News

A movement as significant as criollismo calls for recognizing those who built its foundations—or, as the saying goes, those who laid the first stones.

Created to grant it national recognition, the Day of the creole song is celebrated with festivals, peñas, and serenades, where rhythms like the waltz, marinera, and festejo, accompanied by guitars and cajones, echo across the country.

In the heart of the city, the air is filled with joy as friends and families come together to have a great time. It is as if, by magic, Lima is celebrating once again.

Like many aspects of life, some moments mark a clear before and after. In the case of criollismo in Peru, one such milestone is the Old Guard (Guardia Vieja)—a group of early pioneers who laid the foundation for creole music amid a backdrop of cultural blending and urbanization, primarily in Lima.

These artists played a key role in the creation and solidification of the genre. Let the celebration begin

OLD GUARD

In the early 20th century, the creole waltz began gaining popularity among the working class. According to Gina Moore’s thesis, "La representación del cholo y el indio en el vals peruano" (The representation of the cholo and the indian in the Peruvian waltz), the period known as the Old Guard spans from the end of the Pacific War (1884) to the conclusion of World War I (1918).

The first generation of composers and performers known as the Old Guard included Romualdo Alva Reyes, Emilio Germán Amezaga Llanos, Alejandro "Karamanduca" Ayarza, José Ayarza Gómez Flores, Rosa Mercedes Ayarza, Nicanor Casas Aguayo, Juan Francisco Ezeta, Pedro Fernández, Luis A. Molina, Óscar Molina Peña, Eduardo Recavarren García Calderón, Alejandro Saenz, Fernando Soria, Guillermo Suárez Mandujano, José Benigno Ugarte, and many others.

Rosa Mercedes Ayarza. Source: TVPeru

Rosa Mercedes Ayarza. Source: TVPeru

Although creole music was not well-regarded by the aristocracy during these years, two events helped bring the creole waltz closer to these social circles:

In 1912, Alejandro Ayarza, known as "Karamanduca," launched the musical magazine "Música peruana" (Peruvian music), which showcased various creole artistic and musical expressions, including the cundía, aguanieve, zaña, and marinera. By the mid-1940s, the aristocracy began to embrace the waltz, creating compositions that would endure for posterity.

Another pivotal event occurred in 1912 when the first album featuring songs from the creole waltz genre was recorded. Eduardo Montes and César Augusto Manrique traveled to the Columbia label in New York, and the rest is history: this album received an enthusiastic reception and significantly expanded its audience.

Alejandro Ayarza “Karamanduca”. Source: TVPeru

Alejandro Ayarza “Karamanduca”. Source: TVPeru

NUANCES

Three key characteristics can be identified in this initial flourishing period of creole music:

The non-professionalization of musicians: Singers and composers during this period often improvised or reworked songs. As a result, they did not receive any payment, as there were no formal contracts, allowing musicians complete freedom in their artistry.

Because of this freedom of interpretation, there was no formal authorship for the songs. Musicians often improvised and could perform songs by other composers, making arrangements without needing any authorization.

The songs were performed at family gatherings, fostering a close connection between the audience and the singer. This way, the audience's appreciation for a song was instantly conveyed to the musician.

For criollismo to truly take root in a country like Peru, a guiding figure had to emerge—someone whose compositions would stand the test of time. And that is exactly what happened.

THE LEGEND OF THE IMMORTAL BARD

Born on July 18, 1899, Felipe Pinglo Alva was a young composer from the Prado neighborhood in Barrios Altos, the cradle of national criollismo. Although music was not his primary occupation, there is a consensus among criollos that Pinglo was the one who ultimately defined the form of the waltz we hear today.

Felipe Pinglo Alva. Source: Wikipedia

Felipe Pinglo Alva. Source: Wikipedia

According to "Jarana. Origen de la música criolla en Lima" (Jarana: Origin of creole music in lima) by Fred Rohner, the "Immortal bard" stands out from other composers because his musical work focused exclusively on the waltz and polka.

Through his compositions, Felipe Pinglo revolutionized the waltz, reflecting the social realities of his time by addressing themes of love, inequality, and daily life in working-class neighborhoods. Songs like "Pobre obrerita," "El huerto de mi amada," "De vuelta al barrio," "El espejo de mi vida," "La oración del labriego" y "Mendicidad" are among the anthems of criollismo that emerged from his pen.

A special mention goes to "El plebeyo," Pinglo's timeless masterpiece, whose lyrics continue to resonate today: "el amor siendo humano tiene algo de divino, amar no es un delito porque hasta Dios amó" (To love as a human has something divine; to love is not a crime, for even God loved). This song has transcended borders, being covered by internationally renowned artists such as Pedro Infante, Alicia Lizárraga, Fernando Fernández, Los Trovadores del Perú, Eva Ayllón, Gian Marco, and many more.

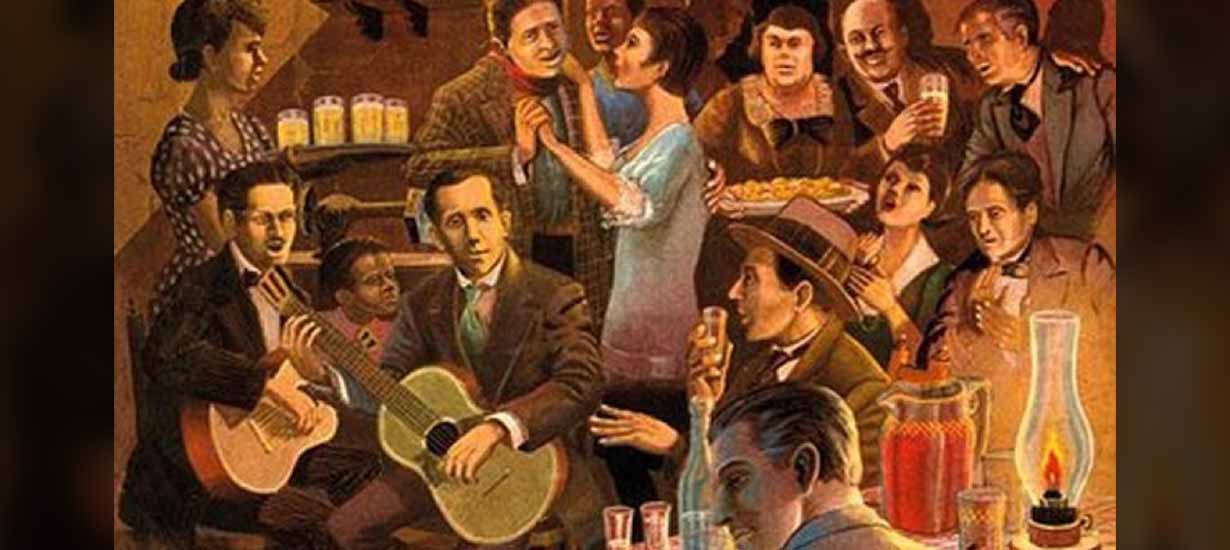

Representación de jarana criolla, junto a Felipe Pinglo Alva.

Representación de jarana criolla, junto a Felipe Pinglo Alva.

The Old Guard played a crucial role in establishing a musical style unique to Peru. These early pioneers of criollismo promoted Lima's musical identity and contributed to the development of a cultural landscape that would eventually gain recognition throughout the country.